Imagine the elevator pitch: an eight-hour psychological thriller set in 1960s Italy, filmed in black-and-white and starring Fleabag’s Hot Priest as an amoral killer whose crimes are witnessed by a cat?

Peeping Tom: a look at Tom Ripley’s seductive lure across six adaptations

As audiences worldwide go wild for Andrew Scott as the latest incarnation, John Forde surveys the legacy of the talented Tom Ripley, cinema’s most enduring grifter.

From this unlikely premise, writer-director Steven Zaillian (The Night Of) has fashioned Ripley, an entertaining and meticulous drama starring Andrew Scott as the grifter’s grifter: Tom Ripley. Now streaming on Netflix, it’s every bit the cinematic spectacle, despite its small-screen home. “Frame every shot and hang it in some gallery,” Haroon says of Robert Elswit’s gorgeous photography, which nods to Italian cinema classics including Fellini’s La Dolce Vita and Antonioni’s La Notte.

Based on Patricia Highsmith’s 1955 novel The Talented Mr. Ripley, the limited series tells the tale of Ripley, an American con artist who’s hired to go to Italy and persuade trust-funder Dickie Greenleaf (Johnny Flynn) to come home. The two become friends (and perhaps something more), to the irritation of Dickie’s girlfriend Marge (Dakota Fanning). Obsessed with Dickie’s life of luxury, Ripley kills him and assumes his identity, a role that fits him like a glove.

Though Ripley’s crimes are cold-blooded, the series has landed to a warm reception on Letterboxd, currently boasting an impressive 4.0 average rating. That response is par for the course for Highsmith’s anti-hero. An immediate bestseller, The Talented Mr. Ripley thrilled and disturbed contemporary readers by making them empathize with a murderer whose crimes (and ambiguous sexuality) go unpunished.

Since then, Tom Ripley has proved irresistible to filmmakers, offering a forensic portrait of class envy, obsession and the sinister underside of that most American of virtues: ambition. Ripley follows in the footsteps of five film adaptations, with Scott inheriting a role embodied by screen greats including Alain Delon, Matt Damon and John Malkovich.

Appropriately for a story about the fluidity of identity, each film is radically different, reflecting the times in which they were made and changing attitudes towards crime and punishment. Although 1999’s The Talented Mr. Ripley is undoubtedly the best-known, the others continue to resonate with audiences, averaging a 3.7 Letterboxd rating—not bad for a 70-year-old killer.

From the start of her career, Highsmith’s prose seemed tailor-made for cinema. Dubbed “the poet of apprehension” by novelist Graham Greene, she conveyed suspense so well that it made her one of America’s most frequently adapted writers. (For more on her life, check out Eva Vitija’s excellent documentary Loving Highsmith).

That said, the author’s subversive narratives often fell foul of film censorship codes, which prohibited villains profiting from their crimes. Alfred Hitchcock’s 1951 adaptation of her novel Strangers on a Train, a thriller about two men who make a plan to commit murders for each other, managed to retain Highsmith’s queer subtext but was given a morally upright ending. Her second novel The Price of Salt, based on her real-life affair with an older woman, was so radical in its depiction of a lesbian romance ending happily that it didn’t reach the screen until 2015, in Todd Haynes’ gorgeous melodrama Carol.

Ripley became Highsmith’s most successful character, and his legacy followed her like a specter. She frequently talked about him as if he were a real person, signing letters to friends as “Tom” and even annotating an award to include his name alongside hers. “I often had the feeling Ripley was writing [The Talented Mr. Ripley]”, she once said, “and I was merely typing.” She returned to her “criminal hero” throughout her life, penning four more novels following his exploits (known as “the Ripliad”).

For Highsmith, Ripley represented both wish-fulfillment—a white male with a social mobility denied to her as a woman—and a dumping ground for her own anxieties and resentments. As a queer artist growing up in a homophobic society, she was an expert impersonator of “normal” behavior. She passed this “talent” onto Ripley: in the original novel, he feels happiest playing Dickie, like an actor convinced “that the role he is playing could not be played better by anyone else.”

Ripley’s amorality made him the perfect subject for post-World War II cinema. Shaken by the atrocities of the Holocaust and the atomic bombing of Japan, filmmakers lost interest in heroic narratives, seeking instead to portray misfits at odds with society.

The first adaptation of The Talented Mr. Ripley reflects this atmosphere of alienation—admittedly with gorgeous Technicolor visuals and fabulous clothes. René Clément’s 1961 Purple Noon combined the pulpy thrills of Hitchcock’s North by Northwest with the restless energy of French New Wave films like Breathless.

For any picture with a potentially unlikable protagonist, good casting is crucial to ensure audience buy-in. Fortunately, Clément cast the (gorgeous) 24-year-old Alain Delon as Ripley—a role that launched him to international stardom.

In keeping with the mood of post-war France, Delon’s Ripley is an existentialist anti-hero, chic in his linen suit and moving effortlessly from one crime to the next, untroubled by bourgeois emotions like guilt. With his chiseled cheekbones, androgynous features and brooding sexuality, Delon was possibly too good-looking to play Ripley. (As Drew writes, “If you look like Alain Delon you couldn’t possibly want to be anyone else.”) This is, to some extent, the point: Delon is so charismatic that audiences follow him willingly into some very bad behavior. “If tom ripley KILLS me,” Carolina says of Delon, “do NOT PROSECUTE HIM, he CAUGHT me SLIPPIN.”

Delon’s Ripley is unambiguously straight, even attempting a romance with Marie Laforêt’s Marge. The queer longing of Highsmith’s story is instead embodied in cinematographer Henri Decaë’s camera, which makes Delon its love-object. Moments after committing his first murder, he peels off his shirt, displaying his lean, bronzed torso. It’s a seduction, distracting us from what should be a horrifying murder scene—in other words, what a skilled con man would do.

Delon’s intoxicating sex appeal has sent many Letterboxd fans into bouts of lust (most of which are too filthy to be repeated here). Even the famously hard-to-please Highsmith was impressed, though she was predictably annoyed at the film’s sanitized ending. Setting a high benchmark for future performances, Delon remains for many fans the best Ripley. “I’ve watched [Purple Noon] for three hours,” Nedzlic confesses, “because of all the times I had to pause it just to take a screenshot of Alain Delon’s face.”

The next adaptation, 1977’s The American Friend by German writer-director Wim Wenders, is based on the third entry in the Ripliad, the 1974 novel Ripley’s Game. A now middle-aged Ripley (Dennis Hopper) works as an art forger, persuading a dying picture-framer named Zimmermann (Bruno Ganz) to help him commit a murder.

Though set in wintry 1970s West Germany—think Volkswagens, flared trousers and bushy mustaches—The American Friend is infused with the moody visuals of American film-noir classics like Nicholas Ray’s In a Lonely Place and Samuel Fuller’s Underworld U.S.A. (Wenders also cast Ray, Fuller and French New Wave director Jean Eustache in cameo roles). Ron calls attention to director of photography Robby Müller’s “angst-dark primary colors—reds and blues so intense they’re near psychedelic, yet grimy, rotting in the thick, muggy atmosphere.”

Many critics, including Highsmith herself, raised eyebrows at Wenders’ casting choices. Hopper plays Ripley as a Stetson-wearing cowboy, channeling the same anarchic energy that took his 1969 biker movie Easy Rider to cult status. His performance embodies a potent (if stereotyped) American-ness. Charismatic and forceful, he effortlessly dominates Ganz’s hapless Zimmermann. Considering the metaphoric implications of this fascinating power struggle, Edgar asks, “To what extent is [Wenders] discussing the harm of US culture at many spheres of society outside of its borders?”

Hopper’s Ripley is unusually compassionate, with a growing fondness for his friend, though there’s no last-minute moral conversion: he has a crime to execute and Zimmermann is the collateral damage. Letterboxd senior editor Mitchell Beaupre praises Hopper’s ability to “subtly display deep emotional pain just as well as charismatic, explosive insanity.” Though originally horrified by the film, Highsmith later told Wenders that Hopper “captured the essence of [Ripley’s] character better than any other film.”

Anthony Minghella’s 1999 movie The Talented Mr. Ripley, Hollywood’s first adaptation of Highsmith’s novel, delivered a tried-and-tested formula for success: gorgeous movie stars behaving badly while living the high-life in glamorous European locations. Filmed entirely in Italy, it’s a lavish spectacle, recalling classics like Hitchcock’s To Catch a Thief and infused with Y2K-era sexual longing. “A 90s Miramax version of Call Me by Your Name as if directed by Hitchcock and Sirk,” SilentDawn reflects. “Strange and enrapturing as a travelogue and a haunting exploration of identity.”

Following Clément’s example, Minghella struck gold with his cast, a roll call of 1990s Hollywood talent: Matt Damon as Ripley, Gwyneth Paltrow as Marge and Philip Seymour Hoffman and Cate Blanchett in supporting roles. The Sun King around whom Ripley orbits is Jude Law, who nabbed an Oscar nomination for his sensational performance as Dickie. Projecting the same charisma and cruel beauty as Delon, Law gets Letterboxders similarly hot under the collar. “Not defending Tom or anything,” Abigail says, “but if young Jude Law was my best friend I’d become obsessed with him too.”

Unlike the cool detachment of Purple Noon, Minghella’s adaptation ratchets up the emotional temperature to a boiling point. Ripley’s sexual attraction to Dickie is made unambiguously clear, including a now-famous bathtub scene between Damon and Law. “The scene where they’re playing chess and Tom asks Dickie if he can get into the bathtub with him invented homoeroticism,” Taz proclaims.

Minghella also plays down Ripley’s sinister side, presumably to make him more palatable for audiences. In Damon’s hands, he’s a sensitive classical musician who longs for love and acceptance. His killing of Dickie plays as a spontaneous act of passion, rather than a cold-blooded act of identity theft. The filmmaker’s compassion for his protagonist gives The Talented Mr. Ripley an apologist slant. By the finale, Ripley is a tragic figure, condemned to kill the thing he loves and remain forever in the closet. For all its charm, the film seems unwilling to consider how being a queer murderer with your own Venetian palazzo could actually be fun.

Capitalizing on the success of Minghella’s film, two further Ripley adaptations were produced in quick succession.

Ripley’s Game, released in 2002, uses the same source material as The American Friend, but sticks more closely to Highsmith’s text. Director Liliana Cavani, best known for the controversial erotic drama The Night Porter, brings a similarly fearless approach to Highsmith. Teamgal calls Ripley’s Game “elegant, suspenseful and well-made, earning bonus points for a terrific Ennio Morricone score.”

In what Stephen calls “a perfect fit of actor and role”, the film’s chief attraction is John Malkovich as Ripley. Iterating on the suave villainy of his roles in Dangerous Liaisons and The Portrait of a Lady, Malkovich has a ball playing a supremely confident psychopath with exquisite taste and an arsenal of one-liners.

Before garotting a mobster in a train bathroom, he asks his hapless accomplice (Dougray Scott) to hold his watch, explaining with utter seriousness, “If it breaks, I’m going to kill everyone on this train.” As the dead bodies pile up, he murmurs, “It never used to be so crowded in first class.” Summarizing Malkovich as a “more violent and overtly threatening” yet “also more humorous and weirdly charming” Ripley, Joe declares: “I can’t think of a better actor for the task of demonstrating man-traps on the floor with a couple of baguettes.”

During the press tour for the film, Malkovich reflected on Ripley’s appeal: “People like him because he does things many of them would love to do. He thinks and acts in a conscious way and always self-servingly. Most people would like to silence their conscience and do the same.”

By contrast, Ripley Under Ground, Roger Spottiswoode’s film of the second Ripley novel, never found its footing. Made in 2003 but not released until 2005, it’s the least seen of the Ripley movies, with fewer than 1,000 watches from Letterboxd members.

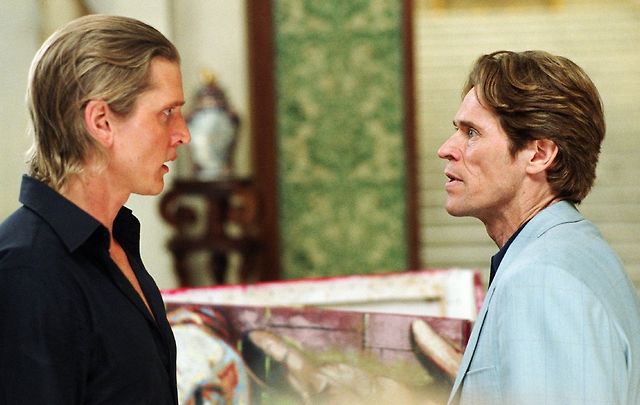

Barry Pepper’s Ripley is a bleach-blond actor living in contemporary London: “more like a charming scumbag than a cunning psychopath,” as Rafael says. When an artist friend dies, Ripley impersonates him to complete a lucrative sale with a dealer (Willem Dafoe).

James writes that Spottiswoode “doesn’t have a grip on the tone”, which “swings between thriller-y elements and almost goofy black comedy.” Though the lowest-rated Ripley adaptation on Letterboxd, Ripley Under Ground is not without its fans. Leonora notes the enjoyably “ridiculous and zany situations like an extended sequence where [Ripley] has to hurriedly wash some very energetic white poodles after they get splashed with blood (?!).”

Which brings us back to Zaillian’s Ripley. With the streamer’s ubiqutiousness, this will be for many viewers their first experience with Highsmith’s character (and a wonderful place to start). For die-hard Ripley fans, Zaillian’s stylish work will reinvigorate familiar material.

As with the other adaptations, Ripley’s success hangs on the charisma of its leading man. Christian remarks that Scott gives “a mesmerizing and compelling portrayal of Tom Ripley,” a man of few words whose pathologies simmer just under the surface. His homosexuality is hinted at, though, as in Purple Noon, he desires Dickie’s wealth more than the man, killing him with the cool disinterest of someone swatting a fly. “Nobody does be gay do crime like Andrew Scott,” Will notes (a nod to Scott’s role as arch-criminal Moriarty in Sherlock).

Zaillian allows the murder scenes to run in real time, often with no dialogue. Ripley’s disposal of his victims’ bodies takes nearly an hour, creating what Connor calls “a slow burn meticulously crafted nightmare that burrows under your skin” and “a masterclass in tension”. The sole witness to his crimes is Lucio, the concierge’s cat, played by a Maine Coon named King. What Messi as Snoop is to Anatomy of a Fall, King is to Ripley—though our money is on King to win in a fight between the two.

Despite its somber aesthetic, Ripley is also very funny, adopting a similarly sardonic tone to Ripley’s Game. Jeff Russo’s elegant score echoes Scott’s chameleonic performance, shifting effortlessly between menace and mischievous wit. John Malkovich even turns up in a couple of scenes with Scott, passing the torch from one generation’s Ripley to the next.

Similar to Purple Noon, Zaillian avoids psychoanalyzing his protagonist. Instead, he puts us in Ripley’s handmade Italian leather shoes and lets us observe his process. Elswit’s frequent close-ups of stone animals guarding the buildings of Rome give us clues to Ripley’s mindset: like them, he’s a predator, coiled and alert, fighting to succeed in the Darwinian struggle of life. (Isabella provides a more precise diagnosis: “Climbing that amount of stairs would’ve turned anyone into the bad guy if you ask me.”)

So what accounts for Ripley’s enduring appeal? In a word, it’s because he is us. “The curious truth in human nature,” Highsmith wrote in her journal, “[is that] falsity becomes truth finally.” Our world now bears out that maxim. Identity is now a marketable commodity, while social media allows us to present ourselves, Ripley-like, as we want to be seen, imitating lifestyles of fabulous wealth.

Highsmith’s satirical portrait of class envy lives on in eat-the-rich narratives including Parasite, Triangle of Sadness and The Menu. Each film has its own Ripley character: an outsider who enters a world of privilege and wins the trust of gullible fools, before exacting a brutal, bloody revenge.

Though not an official adaptation, Emerald Fennell’s attention-grabbing Saltburn is clearly inspired by Highsmith. Like Ripley, Barry Keoghan’s Oliver is a sexually ambiguous outsider who becomes obsessed with Jacob Elordi’s beautiful aristocrat (“Dickie Greenleaf walked so Felix Catton could run,” Clara observes) and infiltrates his rich, bored family. Julia Garner’s stunning performance in Inventing Anna—based on real-life grifter Anna Sorokin, who posed as a European heiress—similarly evokes Ripley’s ruthless ambition.

Far from being just a crime writer, Highsmith was also a prophet, diagnosing the psychopathy of modern identity. (“Somewhere in Hell”, The Wingnut writes, “Highsmith is lighting up a cigarette and howling BIG TIME!”) As The Talented Mr. Ripley shows us, getting what we want is the new religion of our world. The only difference between Ripley and us is how far we’re prepared to go.

‘Ripley’ is streaming now on Netflix.