There are a lot of heartbreaking failures and defeats along the way. It can be very frustrating, but you’ve got to be prepared for failure. You have to get out of the way and park your ego at the curb.

—James CameronFollow the Blue Brick Road: James Cameron on drawing his dreams to life

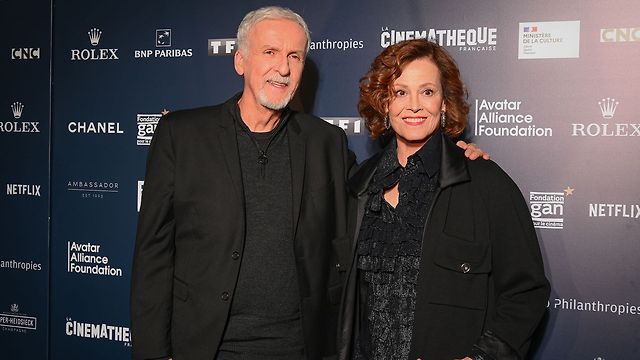

As La Cinémathèque française opens the first major James Cameron retrospective exhibition, Ella Kemp sits down with the visionary filmmaker in Paris to retrace his footsteps and look into the future.

There’s following your dreams, and then there’s bringing them to life to the point of reframing your entire world—and creating new ones—around them. James Cameron will never take for granted two dreams that he had in his youth (literally asleep, not romantically yearning, to be clear), which would commence a lifetime of storytelling and the birth of whole new universes from them. At nineteen years old, he dreamed of a bioluminescent forest, and not so long after that, a metal skeleton rising from a sea of flames.

Cameron, the highest-grossing filmmaker of all time and creator of the Avatar and Terminator universes—and Titanic, if we’re talking Rose and Jack—is in the mood to reminisce on those early images as they, among hundreds of others, are now on display as part of The Art of James Cameron at the Cinémathèque française in Paris, the first major retrospective of the artist’s work.

He is an artist first, filmmaker second (and deep-sea diver third, which, really, is what a lot of the filmmaking is funding). “When I was a kid, I didn’t know I was going to be a filmmaker,” Cameron tells me at the opening of the exhibition in early April. “Drawing was my way of expressing [myself]. I wasn’t drawing for other people. I never showed the stuff too much to anybody.” It was only when Cameron’s Avatar Alliance design director Kim Butts pointed out there may be something worthwhile in his artwork that he let himself look back.

“You follow the progress from some juvenile pieces from grade school and high school, then onward into college and see how they got included in movies I made,” he explains. “Robots, post-apocalyptic themes, bioluminescence and our connection to nature. There’s an organizing principle in the work that I wouldn’t have seen—I just thought they were all scraps.”

For a filmmaker as influential and successful as Cameron, he remains refreshingly humble—at the opening press conference for the exhibition, he tells the sea of mostly French journalists: “I’m surprised at how little I’ve evolved over the years. I have five good ideas I keep reusing in different ways.” That seems harsh but does also speak to the director’s lifelong dedication to the things he loves. He distills it as “a fascination for the real world and the extraordinary possibilities”, then “[processed] through the subconscious, and that comes out in the form of gestural art drawing and painting.” He’ll be the first one to say, then, that Avatar had a gestation period of roughly 30 years.

Cameron has loved the ocean since he was a child—and to this day, he can be counted among the lucky divers who have gone to the deepest parts of it, after building the infrastructures robust enough to sustain the pressure required to get down there. Considering his youth and where all these early obsessions might have come from, he gives me a few options: “Going through National Geographic magazine, seeing pictures of glowing mushrooms and glowing deep-sea organisms, maybe seeing some Jacques-Yves Cousteau film where you move your hand around underwater and everything lights up.”

The filmmaker’s obsessions first came to life in a project that never really became its own world, instead creating the DNA that would animate others. Cameron’s 1978 short film project Xenogenesis, come to life as the mural in which we sit in front of during our one-on-one in Paris, speaks to all the beautiful and strange things the artist built his world around. Like for many movie lovers, it kind of began with Star Wars.

Cameron dreamed up Xenogenesis with fellow screenwriter Randy Frakes and paid attention when George Lucas’s new sci-fi franchise—then just one film—took the world by storm in ways nobody had ever seen. “[Randy and I] were both science-fiction fans and were responding to the success of Star Wars,” he recalls. “We’d read everything throughout the ’60s and ’70s, and found some guys who wanted to put up some money to do a science-fiction film. Of course, instead of doing something small-scale that was appropriate to neophyte filmmakers, we imagined the biggest epic that we could.”

He stands by the script that he and Frakes wrote, but knew where his strengths lay. “As an artist, I thought, the best way to sell this is to create some kind of visual realization of all the creatures and settings,” the director says. “I started drawing and painting like mad, and we were writing together at the same time.” On the page? The stuff of dreams, precisely the ones you know you’ve seen before and can see in the mural: humanoid cyborgs, visions of oceans, and of course, that forest.

“I went back to [that dream] and said, ‘Let’s make a planet where everything glows.’ It’s like a night forest, and the moss and the trees react to you,” Cameron explains of his vision for Xenogenesis. “We came up with this episodic story where each planet had a different kind of motif. It was very Homeric—like the epic of Odysseus, you just go sequentially from one confrontation to another.” It only took 30 years for that idea to reach its fullest form: Avatar.

At the time of writing, Cameron has already devoted fifteen years to the world of Pandora: this place of glowing trees in the Alpha Centauri star system, home to the Indigenous Na’vi people, soon at war with humans ready to colonize and pillage this peaceful, bountiful planet. With two films out, and several more in the pipeline, much has been made of what the franchise has done for the technological advancements in the film industry, the sheer possibilities of what we can put to screen and how (if you’re looking for thoughts on A.I., read on below). But it cannot be underestimated how much of the franchise is about his own connection with Indigenous communities around the world. He knows he’s not the first white guy to have to look in the mirror.

“I was going off of a lot of books on cultural anthropology, mostly written by white dudes, not written by true Indigenous voices—that wasn’t how it was in the mid ’90s,” Cameron says of his early Avatar research. The filmmaker’s deep dive culminated in an 80-page film treatment he completed in 1994, borrowing from “spectacular books” such as Wade Davis’s The Wayfinders, while admitting that “they’re not in the true voice.”

Cameron calls the first film in the franchise his own “white guy version of all that”, describing Avatar as “my screed against colonialism and my cri de cœur about nature and the Indigenous communities.” But what he didn’t expect, once the film came out in 2009, was for Indigenous communities around the world to recognize themselves in these characters and have something to say. “We got inundated by the leadership of Indigenous peoples all over the world, saying, ‘You made this movie about us,’” Cameron recalls. “I was taken aback by that, because I didn’t necessarily know their individual issues, whether it was with extraction companies, oil companies, logging, deforestation or a dam being built that would inundate their ancestral lands. It was a very steep learning curve in 2010 and 2011, where I wound up traveling all over the world.”

Every blade of grass is conceived by a human. We’re proud of that: it’s a very human-centric process. It’s about the human impulse, vision and emotion, and us trying to capture that.

—James Cameron on the Avatar franchise

The Avatar Alliance Foundation was formed in 2013 (and can only be traced online through charity directories as opposed to social media) in response to Cameron’s learnings and conversations after Avatar was released. “I had the sense that, ‘We’ve just made all this money off of this principle, but let’s find out the reality,’” the filmmaker reflects. “Maybe there’s a way to give something back. A lot of people create a new NGO with a sense of ego, but there are people who have been working in these spaces for decades. Why don’t I quietly, from behind, empower them with money and possibly with our involvement if it helps them with media? You have to say, ‘What do you think we should do?’ to the Indigenous leadership, because they know the issues a lot better than I would. How can we work with the people that you’ve already found that you trust?”

Acknowledging the fourteen-year journey since those initial conversations and the start of the foundation, Cameron notes, “I feel like we made progress, but there are a lot of heartbreaking failures and defeats along the way. It can be very frustrating, but you’ve got to be prepared for failure. You have to get out of the way and park your ego at the curb.” The director still admits something of a struggle with criticisms that the Avatar franchise has a “white savior mentality”, but he keeps a self-aware sense of humor: “I mean, Jake was blue, so I don’t quite agree with that. But you have to not fall prey to that idea.” Keep on keeping on, Jim.

Today, Cameron is a New Zealand citizen (pop by the Letterboxd offices whenever you like!) and notes he is on “good terms” with “everybody”, but does not yet have “a lot of big formal alliances with Māori leadership.” The past year has seen him broker relationships with Canadian First Nation communities. “We’re looking at how they deal with colonial issues, and the schools that tried to beat the culture out of them and suppress language,” Cameron explains. “Enable these groups to talk to each other—and then get out of the way.”

All of this work feeds Cameron’s mindset as a filmmaker and a cinephile in his own right as well. His favorite New Zealand movie? Toa Fraser’s 2014 action-adventure The Dead Lands, watched by just 2,209 Letterboxd members and featuring in the four favorites of only two. “It really takes me back to pre-colonial times in New Zealand and imagining Māori culture pre-contact,” he shares. “It’s a fun film and it’s an action film.” Watchlists at the ready.

Three of the four highest-grossing movies of all time were directed by James Cameron: Avatar and Avatar: The Way of Water, number one and three respectively, and Titanic, number four. It is a staggering feat, speaking to Cameron’s peerless mastery of both the emotional insight and technical artistry of filmmaking with numbers that don’t lie. But it’s also why his craft is scrutinized with such detail: when you make a movie about the worrying rise of artificial intelligence in 1984 as your debut feature, The Terminator, and the film industry looks the way it does today, folks will always have some questions.

In Paris, Cameron is more than happy to answer these when it’s all most people can think about at the press conference (despite the exhibition being much more about the pen-to-paper ideas that came before, but I digress). The topic’s always been on his mind: “We’re just now confronting how A.I. might impact cinema and art in general. That’s relatively recent because of generative A.I. But if you go back before generative A.I., there was machine learning,” he explains, drawing a distinction often ignored when just looking at numbers or headlines.

Machine learning has allowed Cameron and his teams to process data and generate models for the forests of Pandora, using the analysis and predictions of the technology to inform their work. “When we have to create a forest, we will generate models of some of the foreground plants as examples, but then we’d actually grow the forest, almost following ecological rules, using machine-learning principles and algorithms,” he notes. “In order to do world-building beyond the immediate foreground, we’d use machine-learning algorithms to do that.”

The director clarifies that the Avatar productions never used A.I. to generate images, beyond using the technology to help quickly storyboard sequences, continuing: “I don’t see that being a part of our process on the Avatar films. I can imagine a scenario where we ask Gen A.I. to create new images for us based on the images that we’ve already created, but we would never use it to create the finished image. The finished image is based on the actors.”

Cameron knows that the Avatar films are the first example folks will turn to if wanting to point to A.I.-generated movies and impossibly detailed imaginary worlds, but he remains steadfast. “It’s all designed by people. It’s modeled by people,” he says. “Some of the distant things in the coral reef and in the forest might be generated that way. But the things that are important are created by people. It’s me with my virtual camera, doing the framing; it’s the actors doing the performance. The art directors created the colors and the designs of the creatures and all the models, down to every piece of the coral reef, every fish.

“Every blade of grass is conceived by a human,” he emphasizes. “We’re proud of that: it’s a very human-centric process. It’s about the human impulse, vision and emotion, and us trying to capture that.”

Time is running out: Cameron will be generous and gracious with what we have and what he can give, so, under the circumstances, it is one, very well-documented favorite film. You can guess the other three. “The Wizard of Oz is still my favorite, because every time I go back to it, I enjoy it just as much,” he says. “It’s timeless, and I think that 1,000 years from now, it will still have that same charm.” I want to ask more, but the filmmaker admits I “got [him] talking”, and there is a message to take back to London for me, and wherever this story may find you.

“‘There is no place like home’? That is not the message of that movie,” Cameron says of Dorothy’s odyssey. “The movie is about the journey of life. You will meet people, and some of them will be against you and some of them will be your friends. Those friends are super, super important. You have to help them and they have to help you and you get through life together. The Tin Man and the Lion and [everyone], they all aggregate around Dorothy, but she also gives back to them and helps them solve their life problems as well. That’s a powerful message for everybody.”

Maybe not quite Ellen Ripley’s journey, nor Sarah Connor’s, but for Avatar’s Neytiri, the face that welcomes us into the Cinémathèque and that turned Cameron’s world a new shade of blue, it sounds familiar. Does Cameron hope the Avatar worlds could inspire that same message 1,000 years from now? “We’ll try our best.”

‘The Art of James Cameron’ runs at the Cinémathèque française until January 5, 2025.